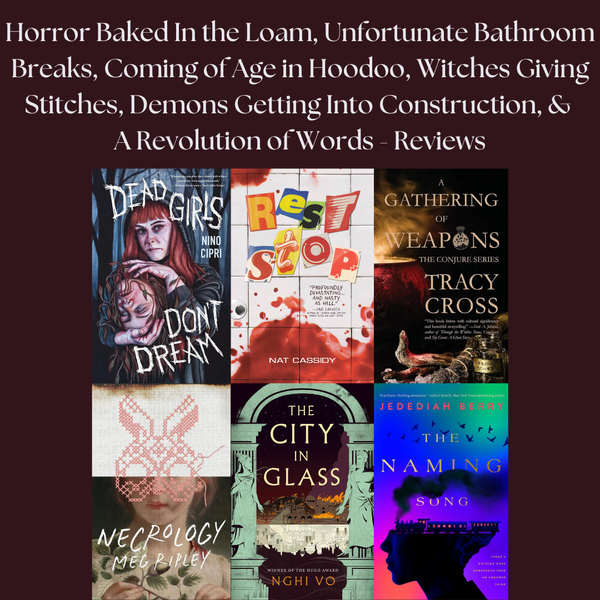

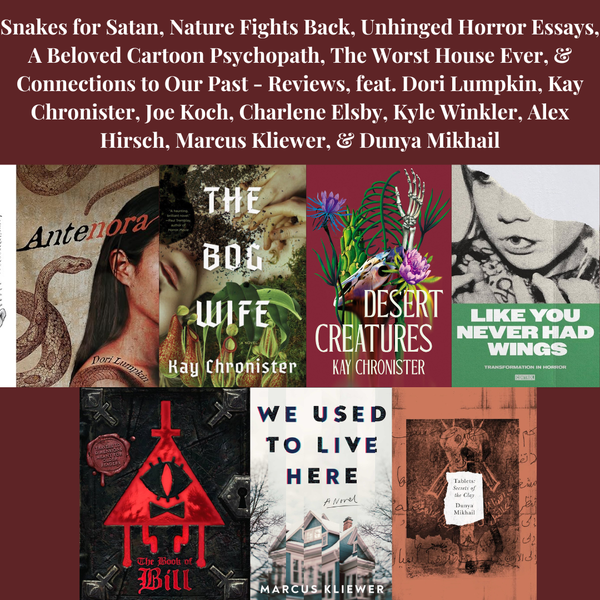

Death Goes on Strike, the Anti-Colonial Moby Dick We’ve Needed for Years, Modern Dating is a Nightmare, Revenge is a Dish Best Served Domestic, and Blasphemy Gets Even Gayer - Reviews

In a bid to get caught up, we’re keeping the review train a-chugging, and boy do we have some fascinating titles on deck today!

Religious trauma, lost political manuscripts from WWII (not clickbait in the slightest), even some gothic revenge of both land and sea with some translated work as well. God I love books. ANYWAY, let’s get started.

Dayspring by Anthony Olivera, Strange Light

There’s something truly magical about reading a book that feels completely indescribable. Dayspring is one of those books.

It’s not every day the gay coming of age novel becomes somehow even more blasphemous, but that’s exactly what Anthony Oliver accomplishes when steeping so much of this story in religious iconography, terminology, and, well, basically telling the story of Christ as told through the eyes of his most impassioned disciple, who also happens to be his lover.

However, the use of this framing isn’t to blaspheme for blasphemies sake. Dayspring is first and foremost a novel engaging with religious trauma, especially what it means for a Christ-like figure to be beholden to faith while also at the mercy of his identity.

This novel is absolutely gorgeous. Written in verse, it’s almost like if Ocean Vuong decided to take on the religious industrial complex when writing On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, or Madeline Miller focused instead on western religion instead of Greek mythology. However, with this being an incredibly queer story, there are places this book goes that maybe a Madeline Miller might be a little hesitant to broach.

Interspersing bits of humanistic wisdom, there is so much revolution present in this novel. When the messiah speaks, the text is colored red, but also serves as the omniscient, progressive voice throughout the book. But I’m kind of getting away from the religious trauma aspect of all this.

Instead of the nitty gritty we so often expect from queer in religion texts of old, the way in which Olivera couches the pain of religious trauma is through the loss of the relationship. Our messiah ultimately has to go to die, as we are to expect in this tale literally as old as time, and our disciple narrator obviously would rather this man he’s in love with not do so. It is within losing his love, and thereby losing his faith, that the trauma truly sinks in for him.

there is so much beauty and pain to experience throughout this novel and I would encourage EVERYONE to experience it for yourself. Dayspring is the kind of novel that is worth the experience of its perceived “density.” Just kick back and let its beauty wash over you. Endless thanks to Sofia Ajram for bringing this book to my attention. I am forever in your debt.

Woodworm by Layla Martinez, trans. by Sophie Hughes & Annie McDermott, Two Lines Press

There is something so uniquely magical about translated fiction, especially within the subgenres of gothic, horror, and speculative fiction. 2024 witnesses the US debut of Spanish author Layla Martinez with her novel Woodworm, detailing the history of a family beset by class difference, misogyny, and odd supernatural forces within their home.

Our two central voices are a young woman and her grandmother, their generational differences providing not only moments of humorous levity, but also some of the most powerful emotional statements throughout the book. The granddaughter has recently returned from spending some time in jail, following the disappearance of a little boy that was within her care. We learn pieces of this incident from both the grandmother and granddaughter, though it becomes obvious that the elder notices a deep darkness within her charge.

Though both women have a hard time acknowledging their shared suffering, it quickly becomes evident just how alike they are as each woman details their stories, with the grandmother filling in the historical pieces of their family puzzle.

Like much of the fiction coming from Latinx communities, Woodworm is ultimately a story about class struggle. The have's versus the have not's. The central family represents the working-class struggle, while the rival family that consistently intersects with them are the political and socioeconomic elite of their village/town. The child who the granddaughter was charged with watching is this families son.

Grandmother fills in just how interlocked these families are, plotting her own mother's experience of living with an abusive husband, as well as the introduction to the "shadows" and darkness that she believes lives within her and her granddaughter. Furthermore, we witness how this class clash influences the way in which the town treats the grandmother and granddaughter as outcast witches.

A fast-paced supernatural gothic that's not afraid to shed light on the horror of reality, Woodworm is truly one of the best debuts this year. Propulsive in its rage and unsparing in the destruction that rage hath wrought, you'll not experience anything quite like this novel, and I HIGHLY suggest going in as blind as possible. It's far more fun that way.

How to Get Along Without Me by Kate Axelrod, CLASH Books

One of my most toxic traits is that I have a hard time reading books that focus on heterosexual relationships. Trust me, I know it's not fair of me, but I've read enough of it by now in my life that you really have to bring something new to the table to engage me, OR, the story has to be super good and engaging.

That's a lead up to my saying that Kate Axelrod's newest story collection, How to Get Along Without Me, is one of such books that shatters a well-tread mold into a billion pieces. Featuring a collection of interconnected characters and stories, Axelrod turns a keen eye on modern dating, taking into account themes of class, mental health, and much much more.

While the larger connections aren't meant to resolve wholly by the end, it's evident that they're not meant to as a means of exploring the nebulous nature of dating in a world on fire.

I may have said that this book mainly focuses on heterosexual couples, however, there is something that feels decidedly queer about Axelrod's explorations. Perhaps this is due to her approach, showing the complex messiness evident in these characters, going against the grain of mainstream rose-colored depictions of love. The overall collection rings a similar note to Little Rabbit by Alyssa Songsiridej and You Made a Fool of Death With Your Beauty by Akwaeke Emezi, preferring the gray areas of relationships over happily-ever-after.

Equal parts heart-wrenching and hilarious, How to Get Along Without Me is another example of CLASH books being the present and history of literary fiction, while introducing a bold and brash new talent.

Death Strikes: The Emperor of Atlantis by Dave Maas & Patrick Lay, Dark Horse Comics

A massive perk of working closely with an illustrator at a bookstore is that we always get some of the coolest new graphic novels. The cover of Death Strikes: The Emperor of Atlantis already arrests your attention, with a blurb by Neil Gaiman and some of the stunning artwork from Patrick Lay and Ezra Rose, but there's something even cooler at play here. Or rather, it's cool to people who enjoy history.

You see, Death Strikes is an adaptation of a long suppressed opera from 1943 by two Jewish artists, poet Peter Kien and composer Viktor Ullmann. Both men were imprisoned in the Terezin concentration camp, a city-like camp in Czechoslovakia that housed all form of creatives as propaganda for the Nazis. It was a ruse to appear as though said creatives were taken care of, while in reality working, starving, and suppressing their work.

Kien and Ullmann were hard at work on rehearsals, hoping to eventually perform the opera within Terezin, but they were sent to Auschwitz before they ever finished, and were killed without witnessing their grand work in performance. A stunning story that transcends genre, Death Strikes: The Emperor of Atlantis tells of a city not unlike Terezin, where a foolish despot keeps his subjects in a state of constant war while he toils away with obsessive math equations as a means to finally "win" his constant war.

Completely fed up with how little people seem to care about death as an abstraction, Death themself announces their going on strike, causing the dead to never actually die, flinging the city in utter chaos and horror. Alongside Death is a breathtakingly genderqueer harlequin rendition of Life, who does what they can to pacify Death and bring the entity of the underworld back to their senses. Also present is an old soldier who attempts to protect the city, while fighting a weary disillusionment, as well as a fierce freedom-fighter whose only reality up until this point has been senseless work and labor exploitation.

What follows is an extremely timely story of greed, fascism, love, and labor amidst a time when violence seems the only recourse. The artwork is absolutely stunning, bringing this phantasmagoric odyssey to life. Plus the end of the book provides pictures of the original sheet music and manuscripts from Kien and Ullmann, as well as essays that detail the history both of Terezin and how folks were able to gain access to what was believed to be lost.

Every bit as charming and fantastical as its premise, Death Strikes holds important wisdom and weight amidst several ongoing genocides. For folks who love comics, history, and lost media, this graphic novel is one you absolutely need to read.

From the Belly by Emmett Nahil, Tenebrous Press

Sea-faring eco-horror has never been so fun.

Emmett Nahil's debut with Tenebrous Press is a slow burn adventure that is strongly anti-capitalist, as well as an unrelenting body horror where nothing feels remotely safe.

When the vessel Merciful (HA!) catches one of their many whales for oil, they find the most peculiar thing within the whale's stomach: a man. Unconscious, but miraculously alive, this stranger is kept in the ship's brig while the team tend to the madness of their captain, a man hell-bent on hunting these whales down.

At the center of our narrative is Isaiah Chase, a sailor working aboard the Merciful who experiences prophetic dreams and the ability to scry with water. As Isaiah becomes intertwined with the stranger, horrific incidents begin to befall the crew. Could it be this stranger's fault? What is the captain hiding as his behavior becomes more erratic?

From the Belly is an extremely disquieting meditation on legacy and exploitation, leaving readers to question the morality of death when the victims are certainly far from innocent. As humans accepted the death of thousands of whales with glee, as a means of furthering empire, how complicit do folks simply trying to earn money in such staggering death?

Nahil offers no clean lines in this discussion, presenting readers with a dark yet cathartic take on aquatic horror, lavishing in the tropes while completely upending our perceptions of these kinds of stories. Perhaps one of Tenebrous's heftier releases this year, clocking in at almost 300 pages, From the Belly is sure to delight horror fans in love with authors such as Ally Wilkes and Dan Simmons.