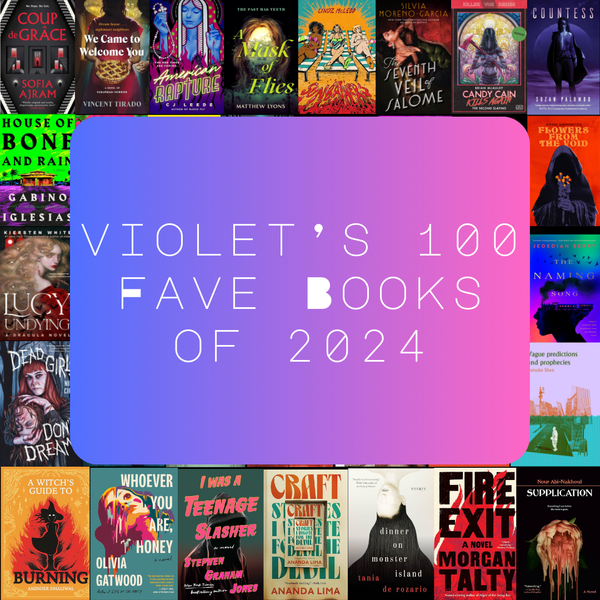

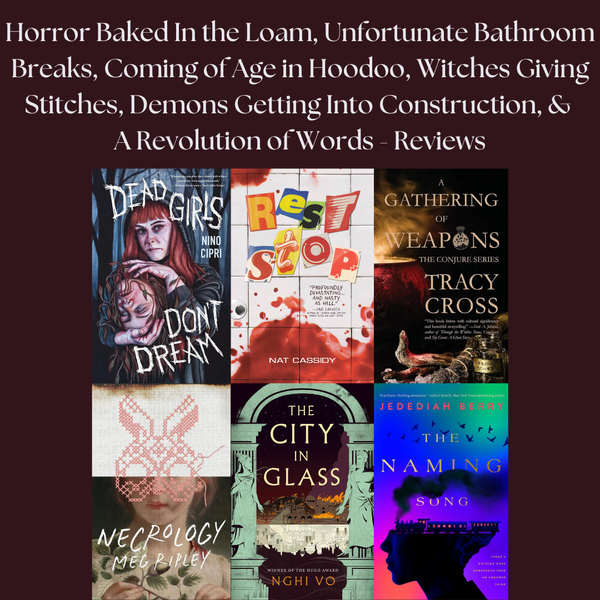

Snakes for Satan, Nature Fights Back, Unhinged Horror Essays, A Beloved Cartoon Psychopath, The Worst House Ever, & Connections to Our Past - Reviews

It's the day after a wedding, and I. AM. TI-RED. This week has simply been hard. Between the truly cosmic and ideological dissonance I witness every day, to gearing up for the very first wedding I've ever been in–it can be a lot.

Thankfully, my saving grace will always be books, and I have quite a few delectable tomes for you today.

So, without further ado: Let's get spoopy.

Antenora by Dori Lumpkin, Creature Publishing

Everyone light up your Sunday best, because we're here to talk about fire and religious trauma–yet again–in the year of our lord, 2024.

Dori Lumpkin, aside from having one of the most delightful names in the community, has been working up to this novella, and the fact of Antenora being a debut longer work is staggering. Because this is an astounding work of queer love and religious horror and violence.

Referring to the circle of hell in which those who betrayed their side or country are punished, Antenora plays upon its title in intensely clever ways, both subverting and affirming the legend, and its religious setting and plot, while delivering further critique in its disarmingly straightforward plot. One could almost intuit its climax, but that's not the point. The point lies in how Lumpkin keeps the reader close with expectation, before unmasking the true horror at the center. It's a device that continues to serve authors attempting to critique society or work through a previous trauma.

Key to our story are two young girls living within a patriarchal and violently strict sect of Pentecostalism, Abigail and Nora. Abigail is our stories speaker, giving direct address to the audience as she regales us with the sordid tale of her best friend, a girl picked out of the herd as the proverbial black sheep. Nora Willet has always lived with a target on her back, as transgressions perpetrated by her family have forever stained their reputation among there far more pious flock. Cue eye roll.

It's within this identity as the town troublemaker that puts the girl at the center of a plot put forth by the corrupt leaders of their community. They spread word that Nora is "possessed" and needs to face the town's own form of "exorcism," which is farm more violent and horrifying that anyone is willing to admit or oppose. It becomes increasingly clear that queerness is the ultimate form of betrayal within the status quo of their religion.

Aside from setting a poisonous snake loose during a sermon, claiming the life of one of the leaders, and killing another in self defense during her exorcism, Nora's relationship with Abigail is seen as the ultimate sin, one which must be punished thoroughly. Her influence upon Abigail is one thing, but for the two to explore and openly profess their love for one another is something else entirely.

I won't go into too much else and spoil the ending, but it becomes obvious that Nora is primed to be perceived as of-the-antenora, due to her criticisms and challenges of their faith. As we learn of her transgressions, we see the extent to which Abigail's eyes–and desires–have been opened by this love.

Antenora is not only a heartbreakingly beautiful love story, but serves as a larger question of betrayal and transgression against one "side" or country. Nora is aware of, and resistant to, the cruel and patriarchal structure of their faith and stands proudly against the system when she witnesses the obscene violence perpetrated upon the women. Despite her fate, Nora boldly stands against these powers, and its a lesson that many of us stand to learn following the most overt and obvious year of displaying hundreds of years of genocide, though we continue to feel powerless in the shadow of those that yield so much from that country's suffering.

We do not have to stand by and allow further exploitation from those who force us to witness their continued cruelty, nor should we stand by and merely pay witness. While its lessons and horror may seem surface-level, there is so much to be found in the darkened depths of this snake's open maw.

The Bog Wife & Desert Creatures by Kay Chronister, Kensington & Counterpoint LLC

Amidst the supernatural thrills and chills of this year, it's always a distinct pleasure to read horrors with a subtler, almost dreamier edge to them. There is continued space for stories the likes of Julia Armfield, Donyae Coles, and as we're discussing today, Kay Chronister, who just this past week released her newest Appalachian gothic, The Bog Wife.

Chronister is an author I've been itching to read since the initial publication of Desert Creatures in 2022. I was drawn to its cover in what used to be my favorite Manayunk bookstore, The Spiral Bookcase, and within the flap's description as a genre-bending eco-horror, the boxes nearly checked themselves. So, once I got the ARC for The Bog Wife, it felt the appropriate time to do a deep-dive.

Centered around an eccentric family, the Haddesley's, The Bog Wife is set into motion by the coming death of their head patriarch. To complete a sacred ritual that has lasted thousands of years, the family must set his corpse within the nearby cranberry bog, where the oldest male sibling will return to the next day to find his "bog-wife," an entity who will help the family sire the next generation of their line.

The gothic aesthetic is present from the jump, with the Haddesley's history and isolation setting up a pastoral, surreal folk horror that trades outright scares for dreamy, incessantly unsettling domestic drama. Tropes arise as a means of highlighting the siblings' disconnection. Due to the isolation imposed by their narcissistic father, they not only rely on one-another, but are pitted against each other–especially the younger against the older–at every turn. Their isolation causes them to appear as relics outside of time, wrapped up in eccentricities that butt up against "modern" society, as is displayed through through actions/choices made by certain siblings later on, especially the middle child, Wenna.

Wenna escaped the homestead a decade ago, doing what she could to acclimate to the world and lead a semi-conventional life. It's only upon receiving a letter from the youngest, Nora, that she comes back to attend the funeral rites as part of the ritual that must take place upon his death. Her presence is simultaneously a balm and accelerant for the eventual "downfall" of the family, as all gothics feature. However, I couch it in quotes because this particular gothic is not a completely somber affair, as the families downfall is ultimately what sets them all free. Their enemy is not a shadowy figure, or even the bog itself, despite how the land retaliates against their settlement, but the secretive empire constructed by their bloodline and upheld by their father.

Because the ritual fails early on in the book, it sets in motion a chaotic unveiling of these generational sins, leading each sibling to take matters into their own hands. However, it's through these seeds of doubt that the truth of their inheritance comes into disturbing clarity. As is suspected in this subgenre, there are dozens of secrets to be unveiled, but unlike more traditional modernizations of the past few years, Chronister deploys a characteristic empathy and understanding that doesn't leave readers despairing by the end of the book. Surprisingly, this one has kind of a happy-ish ending, or rather, one that respects much of the themes it sets up. Most specifically, how land stolen, or even mistreated/used against its will, will retaliate in ways it sees fit.

Much like The Bog Wife, Chronister's debut, Desert Creatures, additionally explores this theme of nature and land doing what it must to protect not only itself, but also retaliating against its abuse.

Set against a post apocalyptic Sonoran desert, a man and his daughter are attempting to reach Los Vegas, which in this universe, has become a kind of mecca where folks with ailments or disabilities can travel to the bones of a saint for healing.

The first part of the book follows Xavier and Magdala, having been exiled from their home. Coming upon a traveling group of pilgrims, they decide to follow this group to Vegas in an attempt to "heal" Magdala's clubfoot. Of course, this being a post apocalyptic world, their hopes unfortunately don't come to fruition.

One of the largest dangers in this world is a form of desert sickness, a madness that slowly morphs into one transforming into something both human and flora, with the humanity quickly diminishing as the transformation takes its hold. This feature is what pivots this contemplative western into a subtle eco-horror, earning the comparisons to Jeff VanderMeer that this book has. Naturally, with very little resources, the band begins to succumb to nature, as well as running into bands of outlaws and the desert sick themselves.

Story shifts when Xavier contracts the sickness and is killed, leaving Magdala to fend for herself in a world so set on indifference. We're then introduced to a priest exiled from Vegas named Elam, who supposedly has the gifts to heal people, but has struggled to successfully do so for years. He has meted a form of peaceful existence following his exile, but that comes to a screeching halt when he finds himself at gunpoint from none other than our Magdala. She forces Elam to help her get to Vegas, as her desire to be healed is stronger than ever.

From here it focuses on their shaky alliance as they traverse the darkest places and people of the desert, before shifting one more time once they make it to the city. Like Bog Wife, Desert Creatures is a tale of nature taking charge, as well as showing its hierarchy over the arrogance of humans that believe they can control or cull it. It additionally explores the innocence and (sometimes) misguided faith we can put in ideas or people or structures that themselves were built on a shaky form of faith. The Haddesley's were forced to have faith and fear their father because he and his ancestors staked their supremacy to their own folly. Magdala has her faith placed in a world that has collapsed, as well as an entity whose own motives rest upon shaky morals and ideas.

We as a species crave order, and as much capitalism will have you believe chaos and dysregulation are the keys to success, this is only to normalize the misery of grind/gig culture. We place our faith in structures that appear to comfort and uphold us and our values, but it's the larger entities, and even connections with nature, that can often bring us back to ourselves; bring us back to regulation.

Both novels, while tonally different, speak in concert with one-another, as Chronister continues to explore how our species' legacy interacts with the nature we have come to exploit and diminish, as well as how our faith in ourselves and structures of power will continue to fail us when their only concern is more pain at the hands of their power. Her prose is dreamy, which serves to offer even more punch to the moments of horror. You will most often find yourself swept up in her fairytale like delivery, so that you're not entirely ready when the jolts come. With two incredibly strong novels and a collection of chilling short stories, Chronister is establishing a unique and human voice within the subgenres of horror, but refuses to allow herself to be pigeonholed.

Like You Never Had Wings: Transformation in Horror, featuring essays from Joe Koch, Kyle Winkler, & Charlene Elsby, Filthy Loot & Control

I've been following Filthy Loot for a little bit now. Through Charlene Elsby and Joe Koch, I found out about this queer little publisher whose books are even smaller. Literally, their tiny books and I love them.

Recently, they put out a call for reviewers, so I was more than humbled to receive a fun little gift package with some of their recent fiction and non-fiction titles, plus some awesome stickers. The first of the books I've been able to crack into so far is probably the one I've been most excited to read since I saw its announcement: Like You Never Had Wings: Transformation in Horror.

Aside from the title being culled from one of my favorite Deftones songs, it also features three writers I very much enjoy–Joe Koch, Charlene Elsby, and Kyle Winkler. All authors I've reviewed in the past, their work has definitely altered my brain chemistry in the past few years, and I say that with absolute love. Koch continues to astonish with their special brand of literary horror and surrealist trash, Elsby continues to write some of the most philosophical and depraved body and psychological horror tales, and Winkler's Grasshands remains one of the most fascinating and engaging cosmic/eco-horrors I've read this year. In other words, I would definitely like to hear what they have to say about transformation as a vehicle in the genre.

I began with this one because much of the work I'm doing in my non-fiction project connects directly with transformation as a theme within horror. I was excited to read what these particular writers had to say about it and I was–unsurprisingly–not disappointed in the slightest.

These essays are fairly short, with the book itself comprising of just over 80 pages. Koch's, "God, I Feel Murder Tonight: Trauma, Transformation, and Beyond the Normal in Horror," is structured as both an academic conversation, but we later learn that there is indeed someone being "transformed" that the narrator is directly addressing as they cut and burn and strip away parts of the persons body. It's a delightfully insightful and horrifying little essay that touches on transformation's connection to transness in horror, especially in the body and cosmic realms. They start by delving into the history of fairy tales, especially the ways in which we've Disney-fied their morality and darker undertones in the originals.

Koch's focus is on "The Frog Prince," a fairy tale we know well, but often misunderstand, given that the frog is murdered in the original tale, only to then become the handsome prince and happily ever after and blah blah blah. As author Amanda Leduc has discussed in her book Disfigured: On Fairy Tales, Disability, and Making Space, fairy tales often brought with them somewhat ableist morality plays. They were typically meant to fix something that was wrong with a person, or at the very least warn younger folks of the dangers of being disabled.

Koch continues somewhat down this train of thought, but instead focuses on the idea that "death in horror, however, means something other than the end." Death is an unknowable phenomena, but it continues to figure into our stories and novels, especially as a way of offering ideas to what may come beyond that "final" act. In the case of the destruction of the frog prince's amphibian body to then give way to a human body, they posit that "trauma is an essential component of shapeshifting and apotheosis." Although it it can be peaceful or welcomed, the act of dying is that final relinquishing of physical autonomy, something we as a society fear with a vengeance. The rest of the essay follows this thread and acts as a brilliant jumping-off point for the collection as a whole.

Moving on to Kyle Winkler's essay, "Shit Mirror," I was drawn in right off the bat with a discussion of the fear of "repetitive sameness." The example he offers is in the uniformity of American subdivisions and the absolute surreality of suburbs. This is a subject I not only get into in my own work, but have discussed when reviewing Gwendolyn Kiste's The Haunting of Velkwood. Through their construction, subdivisions and suburbs were designed to offer a form of universality and comfort for the white folks fleeing cities they viewed as infiltrated by their imagined "Other." They felt a loss of safety, so they fled to spaces as cookie-cutter as they were.

Winkler goes on to evoke the theme of the "shit mirror," itself pulling from the Nine Inch Nails song of the same name. In this theory, the shit mirror is one that would display a "distortion" of what you're seeing. According to him, the shit mirror "cannot, will not, show you what exists but what should exist. What has the possibility to exist." Suburbia becomes its own form of shit mirror due to its uniformity. It shows you what a life of absolute comfort and safety could look like, as long as you conform to white supremacy and don't rock the boat, like, ever. It's a distortion of what the modern-day middle class should look like–at least in the eyes of our societal structures.

The essay continues to clarify much of these themes, but one more quote that really stuck with me–and that's not even scratching the surface because there is A LOT that really stuck with me–is, "We suffer through lots of art that we think will be instructive to us when in reality all it's doing is pinning us down and pinching our skin." I for one am someone who can fall into this fallacy easily. I go into a lot of art seeking some form of instruction, and the unfortunate fact about a lot of mainstream art that's made is that their distortions of what's real. And in a lot of ways that's obvious, but there is a sense of searching when it comes to consuming art, especially horror. We hope for some kind of answer to the chaotic nature of our world and sometimes that is not what's delivered. In many ways that's completely okay, but it's also proving the point of the shit mirror itself.

Finally, we approach Charlene Elsby's "The End of What Is and The Monster It's Become." Surprising no one, this essay builds a lot off of philosophy, being that it's her whole thing. The essay is in many ways a response to an Aristotle quote presented at the beginning:

Now, being that we're talking about Aristotle here, you're likely scratching your head thinking, what the actual fuck? Thankfully, Charlene Elsby is here to help save our brains from entropy at the hands of a long-winded man. She takes a phenomenological approach to her analysis, looking at the essence of transformation in horror itself. She starts by looking at several applications of form as a way of synthesizing transformation and I can't lie, as I was reading this my brain kept doing the "themes" bit from A Bit of Fry and Laurie.

Because, really, what good are they?? Anyway, what follows is an incredibly brilliant breakdown of what transformation ultimately has meant for humanity in reference to that which makes us human. Part of the reason we fear transformation is how inextricably linked "individual consciousness" is with the body to which that consciousness has become inhabited.

Some of the horror transformations that scares us most are those which appear to either sever or elevate this connection. Elsby uses examples such as Jeff Goldblum's transformation in Cronenberg's The Fly remake, highlighting how Brundle's transformation becomes the obsession that ultimately turns him into a monster even he doesn't recognize. I also think of the horrible, yet sort of fun 2000 Kevin Bacon thriller, Hollow Man. Adapting the Invisible Man story for the new millennium, Bacon's Sebastian Caine is already a misogynistic dickwad, but those personality traits elevate with his growing power, leading him to become even more monstrous by the end.

It's hard to fit all of her brilliance in a short review, but the rest of the essay is an excellent breakdown of transformation that sits perfectly alongside her colleagues AND serves as the perfect ending to the collection as a whole. I can't recommend this slim volume enough, especially if you're someone with an academic investment in horror. I'm intensely excited to read the rest of the fiction and non-fiction from this revolutionary little press.

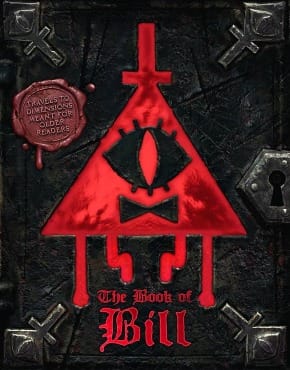

The Book of Bill by Alex Hirsch, Hyperion Avenue & Disney Books

Now, in the completely opposite direction, we travel back to the year of 2012 to revisit one of my favorite animated shows of all time, the beloved Gravity Falls.

Alex Hirsch surprised the ever loving hell out of me when I unboxed this beauty at work. I have no clue how I missed the announcement of his return to the charmingly insane villain at the center of his two-season masterpiece, but boy was I glad to find out about its existence. I'm also glad I bought one of the copies that came in for release week because it quickly became unavailable because apparently publishers didn't realize a massive and rabid fanbase such as the Gravity Falls fanbase would show up in droves for this book.

I have a massive soft spot for this franchise. It premiered a year after I graduated high school, which is already an interesting time for any young adult, but was the beginning of a particularly turbulent time for young Violet. My best friend told me about this brilliant show that screamed all of my best interests while additionally boasting some of the most 90's-00's referential humor I'd seen in a while in animation. It was a pleasant and hilarious watch with voices I've loved throughout my child and adulthood, but once the show really got cooking, I found there was so much more to love about not only Hirsch's characterization and humor, but his storytelling chops as well.

The story of the show's battle with Disney is legendary, from refusing to allow Hirsch to represent certain sexualities and identities, to the limited nature of what he could and couldn't joke about. The man definitely had a lot to work with and only leads me to love the show even more. It's a seamless, powerful story and was already a juggernaut before the final introduction of its maniacal villain, Bill Cipher. Simultaneously charming and disturbingly ruthless, Cipher set the stage for the show's closing episodes of Weirdmageddon, an event where our triangular psychopath attempts to unleash chaos on the denizens of earth to take it over.

It's not surprising that Hirsch has returned to the world for this book, as it remains a wildly popular show to this day. In fact, it was one of my comfort re-viewings during lockdown. I rewatched it twice! That being said, over a decade is certainly the right time to drop an adult-centured deeper dive into everything that is Bill Cipher. Those who were kids when the show premiered are now adults, and those of us who loved it as adults are now...well, even older haha.

The Book of Bill is a brilliant combination of text and image, plumbing the depths of the villain's history, sadistic humor, and further history and backstory within the beloved bizarre town. Hirsch is at his unhinged best when it comes to the humor and tone of this tome, which of course alternates between playful and fun, as well as dark and threatening. You become a captive to Bill as you read the opening pages, written by the fantastically voiced Stanford Pines, which I absolutely read in J.K. Simmons's addictive bass.

What's most exciting about this book is the wealth of easter eggs and puzzles throughout, which, in classic Alex Hirsch fashion, lead to further pieces of information and jokes. The artwork also features familiar faces such as the legendary Trevor Henderson, who concocts several nightmares within the "Cryptid" section of the book. There certainly aren't many moments where the signature Hirsch humor isn't on full display, playing with well-known phenomena and names throughout horror and weird fiction, with "Guillermo del Torso" being a personal favorite.

If you're as big a Gravity Falls fan as I am, which if you follow me or are my friends, you likely are, then you need this delightful continuation of the beloved universe with plenty of appearances from all of our favorites, as well as some exciting new lore and background. The great news is it seems like the book is more readily available again, so get out there and check it out!

We Used to Live Here by Marcus Kliewer, Atria/Emily Bestler Books

Speaking of mind-bending puzzle-boxes, let's talk about We Used to Live Here.

Another title I missed out on until it was brought to my attention to by the lovelies Sadie Hatmann and Peg Turley, I was excited to learn this was a darling of the r/NoSleep subreddit. It appears 2024 has been the year for writers who made their start on the influential platform. Marcus Kliewer apparently had been building upon this concept for a little while before it was picked up by Atria, and already has a Netflix adaptation in the works, starring...Blake Lively?

I only include that here because the two main characters of this novel are queer women but, hey, Netflix is nothing except consistently clueless. Blake Lively is certainly capable of playing the paranoia that is necessary for Eve's character, but part of me hopes she'll be playing the wife of the inciting family because casting straight actors to play queer is tired at this point.

RANT OVER. Let's jump into this whacky thriller, shall we?

Couple Charlie and Eve are house-flippers, and their current project is an old house in the kind of picturesque neighborhood that houses these sorts of horror stories. One day, Eve answers the door to a family whose father claims he used to live in the house and was wondering if he could bring his family in to show it to them. Unsure of what else to do, Eve lets them in and quickly regrets her choice as the family seems...off. There are plenty of red flags, but when the daughter, Jenny, disappears in the basement, it becomes clear that something very strange is going on in this house.

When Charlie returns to the house, it seems as though all will return to normal. They find Jenny and are ready to leave, but then Charlie invites them to stay for dinner, and it's at this point that everything falls to hell. A dangerous snow storm is sweeping in, closing the only bridge in and out of the area. Following some other odd encounters, everyone finally goes to sleep, however, when Eve awakens, Charlie is gone and she can't get ahold of her. It's from here that the true insanity of the novel unfolds.

So, I must say that part of my experience with the book was colored by the fact that I listened to the audiobook, which was fantastically done, but I was very confused by what sounded like morse code in between the additional documents acting as occasional interludes. I texted Peg and found out there are little puzzles and clues in this book as well. I have yet to dig even deeper into what these little clues mean, but it's absolutely an enjoyable aspect to the book. Being a big found-footage fan, the interstitial "documents" really added to the mystery and absurdity of the novel.

To call We Used to Live Here a haunted house tale feels wrong, because it is so much more than that, but to say more would be massive spoilers for the story. Simply know this is a unique ride that requires your curiosity and attention. It carries the feel of the best creepypastas and r/NoSleep stories, while setting out its own identity at the same time. Go in as unaware as you possibly can, trust me, it's worth the ride. It's unnerving and creepy and refuses to explain itself in the most exciting way.

Tablets: Secrets of the Clay by Dunya Mikhail, New Directions

To close out on a non-horror note, I bring your attention to a poetry collection that has done something incredibly exciting. Tablets: Secrets of the Clay presents poems juxtaposed with some of the oldest writings and tablets, found, translated, and translated again by Iranian-American poet Dunya Mikhail.

The poems are not translations themselves, but responses to the images themselves, highlighting Mikhail's anxieties, loves, hopes, and fears in the current cultural moment. These poems are simultaneously awe-inspiring and heart-breaking, as you come to see the ongoing genocides through her eyes, while also attempting to maintain hope.

I did not know what to expect from this particular collection, but the concept of trying to bring new life to some of the most ancient forms of connection struck me so much I needed to read it. The poems are fairly short, and each section has a handful of tablets, moving throughout the general theme that Mikhail puts forth, providing something unlike anything I've seen in poetry yet. There's so much love and care present in its pages.

I cannot recommend this book enough, for poetry fans, and probably even fans of communication and linguistics studies, it's truly unique and beautiful.

I know this was another long one, so thank you so much for reading, and I hope to be back very soon. It's been tough to write, lately!

Love y'all, stay safe and vigilant.