"Soon, you won't remember anything. Your real name, your superpowers. You won't even remember that you're dying." An Exploration of Race and Class in "I Saw the TV Glow"

I'm going to try something a little different today. Earlier this year I wrote a piece reviewing Mike Flannagan's stellar Poe adaptation Fall of the House of Usher, which leaned much more toward my old school cultural criticism roots. Not that those roots have deteriorated, my reviews definitely continue to skew in that direction.

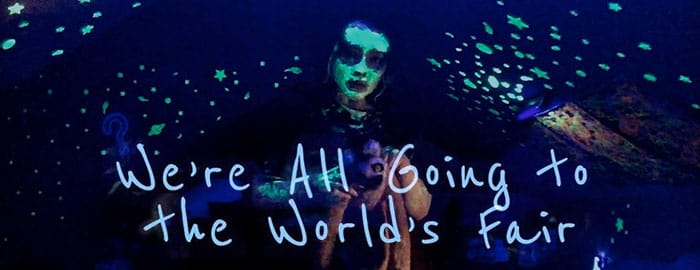

Today I wish to do the most stereotypically trans thing I could do currently, which is to talk about Jane Schoenbrun's recent film, I Saw the TV Glow. The most recent of the indie horror darlings gracing our silver screens, this genre-bending film has caused quite a bit of buzz since its wider release earlier this summer, and for good reason. With it's recent release to Video On Demand, more folks will have access to it and be sitting with its gorgeous and heartbreaking images.

For those who aren't intimately talking with me on a daily basis, you won't know that I've been slowly working on a collection of essays focused on my personal journey with gender dysphoria and how the subgenres of cosmic, body, and folk horror have assisted me in my further gender and trans journeys. This has been quite an ambitious project on my part, hence its current slow progress.

Part of this book zeros in on the time span of the late 2000's and earlier 2010's, which some will remember as the time where internet horror and found footage truly converged at a specific intersection. Creepypastas were at their most popular, forever changing the way in which written horror was displayed and disseminated. Several of these intersections would make way for the current surge in analog horror content we've seen on YouTube in the past several years, with popular series such as Channel 52, Gemini Home Entertainment, the classic Marble Hornets, and yes, even Five Nights at Freddy's, in its inception.

A similar trend has found its way into books with several horror novels this year playing with the artifice of found media, displaying video tapes on their covers, and contemplating, maybe even mourning, these previous forms of media creation, while working off of the precarious subjects of memory and youth. Paul Tremblay's Horror Movie is an excellent example, as well as Kiersten White's outstanding and emotional Mister Magic; itself a recontextualization of topics put forth in Kris Straub's infamous "Candle Cove" short story. Gabino Iglesias and Andrew Cull compiled an entire story anthology focused on found footage as its central theme, bringing together a stacked roster of authors who ingeniously melded a hyper-visual medium with the written word.

All of this is to say that as many within the generational span from Gen X to parts of Gen Z contest further with rapidly shifting technology and media, it's no surprise we find ourselves harkening back to technology and media that seemed much...simpler. On the other hand, this advancing technology allows for many to return to times that require their own form of critique, analyzing ways in which the television, movies, political climates, and other factors effected our unique experiences, as well as what that means for those of us who create art.

Nostalgia is a hell of a drug, causing folks to get lost in dreaming of times that may or may not have existed, causing further distress from the panic that comes with not trusting our own memory. Were those positive and wistful emotions true to our lives, or were we merely attempting to protect ourselves from more complex, or potentially darker, truths? Contemplating Schoenbrun's initial debut, We're All Going to the World Fair, these themes appear central to their work.

While I could write an entire exploration/breakdown of the myriad overt trans messages within I Saw the TV Glow, there is a topic I'm more focused on in this particular piece, something that I've been thinking about a lot in recent weeks. Today, I wish to discuss how Jane Schoenbrun's work has a lot of interesting things to say about class, and, in the case of I Saw the TV Glow, race.

We're All Going to the World's Fair and a Class of Loneliness

To quickly return to Schoenbrun's debut, the subject of class is something that, like IStTVG, remains persistent in the background of the film. While viewers aren't shown much in the way of Casey's world outside of her bedroom, the few images and settings we are shown reveal what could be considered a fairly working-to-middle-class upbringing. Her modest suburban house is predominantly surrounded by woods, with a shack briefly displayed during a bout of her insomnia, and her room doesn't appear to be extravagantly decorated.

In regards to her relationship with her parents, we don't even really see a physical manifestation of them, rather the father's booming voice when he scolds Casey from downstairs. There might be some potential clues toward him being working class, but we can glean from the modest housing and even Casey's clothing choices, that this family is nowhere near wealthy.

For those who came up in working or lower-to-middle class families, there was a certain boredom or ennui that frequently arose from sitting at home. Especially if you lived in rural areas where the closest excitement both cost money and was, at the very least, a half hour of transport away. Once lots of families in the U.S. gained access to desktop computers and the internet, this ennui shifted toward a new sense of exploration, though not necessarily acting as a balm for the loneliness felt by those without access to a more lavish lifestyle.

In World's Fair, Casey is drawn to the titular YouTube challenge because she views it as a way to connect with a larger web of creators, while also potentially finding a way to transform herself and her surroundings from the trappings she currently contends with. To bring up the dreaded c-word, many folks who exist on the lower rungs of society under capitalism look to the access to resources that celebrities and billionaires acquire, giving feeling to a jealousy, regret, anger, resentment, that arises from that sense of lack. If only I worked harder, or pulled my bootstraps tighter, or did better in school–no matter what spiral you go down, these thoughts lead to similar places, as well as a feeling of immense loneliness and isolation that people don't always realize effects kids in tremendous ways.

The World's Fair challenge offers Casey a chance at difference, or, at the very least, a community that exists outside of her own isolation. This ethos likely gave birth to the Influencer movement we are in today. A way for anyone, no matter your means (allegedly), to become the "next big thing." As the years following COVID have revealed, the folks who most often become influencers are those who have no qualms with social climbing, with the resources/energy to do so in a full-time capacity. However, for someone like Casey, this feels like a way out. It feels like a way to escape the alienation that claws deep inside of her.

For trans folks growing up during the late 90's and toward the beginning of the 2010's, the internet became our way of forging connection, even when we attended schools or were surrounded by neighbors. Our difference served as the tool for our alienation and loneliness because we didn't have the access and resources perhaps our more wealthy peers did. In my childhood cul de sac, there was a period of time where many of us would hang out and play together, whiling away the hours of summer simulating house, acting with dolls, action figures, and blurring lines of gender and sexuality in the stories we told. We were lower-to-middle class kids with nothing to do, but we had each other, at least until we got a bit older and social order had to be established. Up until that point though, we were our own little (secretly) queer brigade. Gender wasn't something we focused on, and I'm forever grateful to them for that.

It's within these themes that the current of class presents itself in World's Fair, showing the light, dark, hope, connection, alienation, and even danger that could come with being a young person on the internet during those times, attempting to suss out online literacy for ourselves, while doing what we could to keep ourselves safe. Schoenbrun captures this with such acuity, that the audience that most responded to this film due to the clarity with which we saw ourselves. While the transness of its story is potentially subtler than IStTVG, we see many of our own origin stories in Casey's experience, especially in how she engages with class. It's within their sophomore effort, with more of a budget and an even larger vision, where much of Schoenbrun's ethos as a storyteller truly comes alive.

I Saw the TV Glow - A Parable of Trans & Class Struggle

When I first saw the image of Justice Smith and Brigette Lundy-Paine sitting side by side and staring at a television screen, I was initially elated to learn that a new Jane Schoenbrun movie was coming, but additionally that Smith and Lundy-Paine were the main stars.

Regardless of what many people on the internet say, Justice Smith is a powerhouse of an actor. He's appeared in several prominent films, and while many of them are not necessarily good movies, he remains a highlight in each one. And though I've never seen Atypical, I've seen enough of Lundy-Paine to know that their energy is magnetic and commanding. The fact that both are queer actors is a tremendous plus.

The opening of the film will ring familiar for any public school kid coming up through the late 90's and early 00's, as we're introduced to the younger version of our central protagonist and narrator, Owen, played by Ian Foreman. He stands in the middle of a game of Mushroom, where the children fling a parachute into the air and then sit down on the ends, creating a domed air pocket that they can inhabit. The shot is gorgeous, as Owen gazes awestruck at the beautiful, trans-colored parachute, acting as a reject of the neon colors of the 80's. All the while, these images are scored by Singaporean artist yeule's gut-wrenchingly transcendent cover of Broken Social Scene's "Anthems for a Seventeen Year-Old Girl" playing in the background.

For those unfamiliar with this song or band, Broken Social Scene was a celebrated Canadian music collective boasting members from the likes of METRIC, Feist, and Stars, to name a few. "Anthems for a Seventeen Year-Old Girl" is one of those canon indie rock songs that has stood the test of time for its earnest, wrenching lyrics and meditative instrumentation. It has appeared on many of my sleepytime playlists. Sung by METRIC singer, Emily Haines, "Anthems" is a song that has been read as a woman mourning her younger self, likely to be seen as an outcast, or someone who eschewed social norms, but eventually caved to the pressure of traditional femininity to survive the horrors of high school. Sound familiar?

yeule's cover is equally meditative, though somehow managed to make the song even more achingly gorgeous and heartbreaking. With more instrumental layers than a Cake Boss cake, glitchy, gender-bending vocals that loop, contradict, and harmonize with unique melodies, and a decided lo-fi quality befitting of the film's mid-90's, analog feel, it stands as one of the greatest covers of a song to date, while also subtly introducing the main themes and tragedies of the story.

Anyway, back to the beginning. Mushroom was one of those games that I'm sure was played in more well-off school systems, but it's most remembered amongst us who experienced grossly underfunded gym classes, prompting a game that's so built upon imagination and simplicity. After Owen's somber introduction narration, we come to a parent-teacher night, or maybe an orientation night, where his mom (Danielle Deadwyler) is speaking with one of the teachers while Owen wanders off to explore the school, with its muted color tones and vacuous hallways. He comes upon Maddy, whom he earlier saw holding a book about The Pink Opaque, a television show that he's become drawn to, but has no way to view due to his patriarchal father (played with expert menace by Limp Bizkit's Fred Durst).

Both share an interaction that's at first very awkward, but soon Maddy recognizes a need, or reaching out, that Owen is looking for, coming over to talk more about the show and hatching a plan for Owen to sneak over to her house to watch the show together. We then cut to the ride home where Owen broaches this topic with his parents and we witness the extreme power imbalance between Brenda and Frank. Owen asks her first if he could have a sleepover with an old friend he hasn't talked to in a while–the cover he's using to get to Maddy's. We can tell she's hesitant to bring it up to Frank, knowing he's prone to say no. All we see is a shot that looks to be from Owen's perspective, being his head is in his mother's lap, looking up to Frank who turns his head menacingly and doesn't respond, but we later see Owen being dropped off.

There's never much of an indication of the true relationship between Frank and Brenda, other than the sense that he is a stepfather of sorts, and a later scene where Owen screams "This isn't my home! You're not my father!" to him, though this can be read as Owen attempting to reject the world he's currently living in. However, it's obvious that Frank is an extremely violent force prone to rage, or at least downright simmering resentment. I don't think Durst speaks once in this role, directly contrasting with his larger-than-life persona in Limp Bizkit. I even totally forgot he was set to star in the film, only remembering once the credits rolled, because of his very physical transformation.

In fact, we don't see much of Frank once it's revealed that Brenda is extremely sick, most of the care falling to Owen, leading to Frank's seeming indifference toward Owen once she's gone–with the exception being where Owen attempts to climb into the TV, toward his true self, which Franks absolutely DOES NOT want, further characterizing him as an agent of Mr. Melancholy, the terrifying antagonist to both The Pink Opaque and "reality." In a way, Frank can be read as his own agent of white supremacy, being that he represents so much of the most virulent aspects of what white men tend to become under its oppression, with Mr. Melancholy acting as the overall structure itself, hell bent on keeping Owen away from his truth.

This brings me to a lot of the thoughts I've been having of late. While Schoenbrun likely didn't set out to make a grand statement on class or white supremacy, they understand the nuances that come with how those structures effect all trans people, not merely white trans people. It's natural for these topics to come up when discussing transness and queerness, but the choice to characterize Owen as Black appears to be it's own statement, especially considering where the film goes and its tragic ending.

Huge warning for spoilers from this point forward, though if you're reading this, you've likely seen the film or don't care about spoilers haha. EITHER WAY YOU'VE BEEN WARNED.

"There Is Still Time" - What I Saw the TV Glow Says About White Transness & Access to Trans Care

Earlier I was discussing how class appeared in World's Fair, as commentary on the isolation that can seldom stem from living lower-middle-class in rural areas. In I Saw the TV Glow, Schoenbrun widens the scope, placing the story in what looks to be a typical suburbia, though perhaps not as idyllic as some may appear.

Throughout the film, we witness the growing/evolving friendship between Owen and Maddy, especially as Owen makes it a ritual to come to Maddy's for viewing parties. She also tapes episodes that he may otherwise miss, allowing for Owen to view them repeatedly and further immersing himself in this world that feels so familiar. Both are deeply invested in the show and the tidal waves of emotion it evokes in their experience. Like Owen, Maddy is shown to come from a fairly tumultuous home, where she must hide Owen from her father who, similarly to Frank, appears to have a massive mean streak.

It's within these scenes of the two sleeping in the basement together that we witness some of the more tender moments of the movie, with one particular exchange seeing Maddy trace the ghost insignia that the characters of The Pink Opaque share as a form of power, protection, and connection to one another, onto Owen's neck. These scenes have their own anxious tension, though that's more due to potential neurodivergent communication than actual romantic tension. I mean, if you're thinking that Owen and Maddy are meant to be coded as a couple, I'm not sure what movie you watched. Maddy's movement to trace that insignia is not only a showing of trust, but more importantly, care for her friend, wishing to protect him from this larger world.

What we come to learn is that our main protagonists are actually the two main characters of The Pink Opaque, Isabel (Helena Howard) and Tara (Lindsay Jordan), with their presentations of Smith and Lundy-Paine being a plot enacted by Mr. Melancholy to keep them separated from one another, but also disempowering Isabel by altering her gender, thus fostering the feeling of wrongness/dysphoria that Owen experiences throughout the first half of the movie. The reason that he and Maddy are so drawn and emotionally invested in this show is due to the fact that their witnessing their story reflected back at them through the TV.

Returning to the forementioned sequence of Frank keeping Owen from climbing into the television, this reveal makes all the more sense, showing Owen as perhaps experiencing a moment of breaking through Mr. Melancholy's oppressive "real world," furthering the theory that Frank is himself an agent of this oppressive system. Queerness in men is typically frowned upon no matter your race, but Black queerness in men is its own danger, let alone for Black trans folks and the amounts of violence and vitriol they receive for merely trying to survive this hellscape we live in. I feel it's within Smith's performance that so much of that underlying experience is given real weight.

Now it's time to dig into the not as comfy stuff, as we delve into the ways in which the film highlights–and perhaps critiques–the disparities between white and non-white trans and queer folks.

Maddy makes it clear early on that she's looking to run away from their hometown, considering the tenuous status of her home and family life, however, she tries to convince Owen to come with her, as a way for the duo to take care of each other, together. Despite Owen's obvious desire to do so, he faces real consequences and restrictions as a Black man in a majority white suburban area. It becomes clear that he doesn't have any close friends or acquaintances with the exception of Maddy, plus with his mother facing sickness and potential violence from Frank, he feels an understandable responsibility to protect her. All of this aside, if the two were to run away, how much can they truly protect one another?

Despite their shared neurodivergence, Maddy is still white, and has that slight bit of safety compared to Owen because of the color of her skin. What happens when they encounter the myriad situations that she has access to, but Owen does not? She obviously cares for him and is characterized as someone that would fight like hell for him, yet white supremacy is something that operates and oppresses on larger scales than one person, let alone two where there's already power imbalance regardless of their allegiance to one another. We can only hope Maddy would step up and push back against her whiteness to protect Owen, but as the broader queer community has unfortunately expressed often–when the going gets tough, most folks turn tail and run.

As any queer text worth its salt has reported over the last several decades of struggle, white queers are notorious for working against the betterment of all other non-white counterparts–especially cis gay white men and, sometimes, cis white lesbians. Exceptionalism is a scourge that causes anyone to turn on their communities, but throughout queer history, white supremacy has made it endlessly enticing to work toward exceptionalism, even in this era where "gay marriage is legal." No matter what laws get put in place, there are hundreds later proposed to strip the tenuous protections of millions right behind it, make no mistake. This is why Maddy's next moves are all the more heartbreaking.

It's revealed Maddy runs away without Owen, or at the very least disappears, leaving behind her destroyed TV, signaling her rejection of the "real," trying to find her way back to The Pink Opaque. Obviously this is a massive blow to Owen, as his one buffer against this horrific reality is gone, while also struggling with the loss of his mother and complete vacuum of loneliness that Maddy leaves in her wake. It's a shift in the story that further highlights real discrepancies between how they both move through the world, with Maddy ultimately stranding Owen and Isabel in a place that works to destroy them. Yet again, solidarity falls to the structures set to disintegrate it. However, the plot shifts again, because Maddy comes back.

Jumping forward several years, Maddy reappears to Owen, thought likely channeling far more of Tara, as their presentation is now more androgynous. Owen is naturally elated, though it's clear that Maddy/Tara is much more withdrawn than before, signaling their being back in this world is effecting them in a real way. Kind of like when an out trans person returns home following transition, having to face the disconnect of their newly comfortable presentation with a place that caused them immense trauma and discomfort. However, again, being able to go between the two worlds is something Maddy/Tara has potentially easier access to as a white queer person, even in this fantastical world and metaphor. So they take a trip to the local queer bar where Maddy/Tara can safely talk to Owen.

It's revealed that Tara was able to get back to their body that Mr. Melancholy buried when enacting his horrifying vision, clawing their way back into the world they belonged in. They're not able to discover Isabel's body, as Melancholy made sure to hide her away from Tara so as to keep their connection and power severed. They try to break through to Owen that this world he's still inhabiting is not real, and the longer he stays there, the more of his energy will become consumed by Melancholy. As a last ditch effort, they ask Owen to meet them in the gymnasium of the old school, hoping to bring him out of the conditioning that has its claws in him.

Despite his reservations, Owen arrives at the gym to find Maddy/Tara in an erected planetarium, where they deliver a powerful and emotional monologue further detailing their story, connection, and why Owen must return with them. Interspersed are memories we haven't seen of the two before, with a standout being a sequence where Owen tries on a beautiful purple slip dress, coming out to show Maddy, with the two then embracing in one of the most wrenching images of the film, eventually cutting to Owen once again in the dress, following Maddy/Tara through the football field, back toward The Pink Opaque.

Yet, still feeling utterly trapped by his circumstances, Owen stops and runs from Maddy/Tara, completing his rejection of The Pink Opaque and the reality of Isabel's identity, thus rejecting her transness in favor of safety. We witness the utter devastation in Tara's eyes as they realize they've completely lost their friend to Melancholy, continuing onward alone.

"I'm Dying!! Help Me!!" - The Brutal Truth at the Center of Schoenbrun's Ending of I Saw the TV Glow

I don't give a good god damn who you are, realizing your gender dysphoria is one of the most terrifying experiences you face as a trans person. While the dichotomy of euphoria and fear exists as well, once that euphoria wears off, the true weight of this realization comes crashing down upon you. It's likely akin to armchair philosopher's realization that they're but a mere speck of dust in regards to the wider cosmos, yet, the reason realizing dysphoria can be that much more terrifying is you realize how much danger you may now find yourself in.

It's part of the reason I often continue to dress in a more masc presenting way in my current home of Bucks County, PA. Flanking me on all sides are towns that are either full-blown racist and transphobic, or full of white, "well-intentioned" liberals. I am beyond fortunate and privileged to be able to stealth myself in this way. Not many are able to easily, or successfully do this in towns such as these. One could argue that trans people are not safe anywhere, since places considered more trans-friendly like Philadelphia continue to witness the murders of Black trans women far too often for sanity's sake.

Some viewers may view Owen's choice to remain in "reality" as cowardly, but this choice is what sets IStTVG apart from most Hollywood trans films. Instead of attempting to wrap the film up in an affirming, pretty little bow, Schoenbrun commits to the themes of class and race disparity by displaying the reality that many trans people, especially non-white trans people, remain closeted due to very real fear of violence and ostracization. Even if you're cis, consider with me for a moment–you are someone who statistically and literally faces a considerably larger risk of violence, poverty, housing insecurity, and so much more if you choose to pursue transition, whether social, medical, whichever you choose. Would you take that chance? Obviously many refuse to give into that fear, flipping a big-ole bird at white supremacy, making them truly some of the bravest people on this planet, but not everyone possesses that strength, and with good reason!! It's scary as hell.

Owen considers his entire life up until that point. Regardless of the existence of The Pink Opaque, there is that .01 chance that Maddy/Tara is making this up and then he's completely at the mercy of a world that would rather see him erased than happy. If Isabel and Tara were to be reunited, regaining their powers, they were already once defeated by Mr. Melancholy. Who's to say it doesn't happen again? Why not merely suffer through the discomfort and dysphoria if that guarantees safety? Wouldn't most of us choose safety over death? ESPECIALLY for a non-white person statistically facing more danger?

This is the brutal but understandable truth that Schoenbrun acknowledges through Owen's choice. We fast forward twenty years and see Owen in a contented, though perhaps somber, life. Despite it all, he is kept safe within this world designed to trap him, though obviously aged beyond his years and struggling with health issues, he appears to be in no immediate danger. Even as Tara attempts to reach him with messages of "There is Still Time" throughout the neighborhoods, he stays in the safe existence. We follow him to his job at a new activity center for families, built within the skeleton of the old school, featuring the benevolent villains of The Pink Opaque. The games almost function as shrines to the characters, further drawing power into Mr. Melancholy, mocking and leering at Owen as he enters into his workplace.

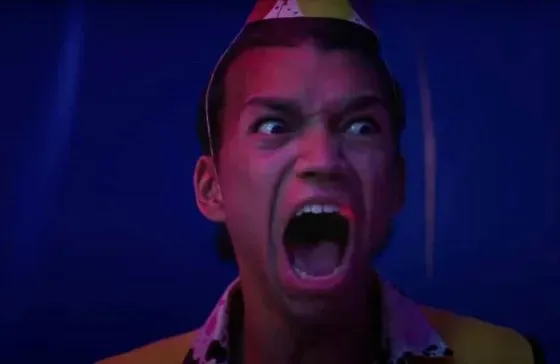

Overseeing a birthday party hosted in their claustrophobic private event room, Owen finally snaps, screaming at the top of his lungs, "I'm dying!! Help Me!!" over and over again in truly the hardest sequence of the film to watch as a trans person. In this moment of clarity, Owen becomes aware of the fact that Isabel's body is likely further dying, that he's almost out of time. His coworkers around him suddenly become lifeless as he screams, as though the simulation has paused. He runs to the bathroom, contemplating his reflection, slowly unbuttoning his shirt to reveal the fissure where Mr. Melancholy had removed Isabel's heart. He opens it to reveal a purple-pink glow that emanates in a moment of gender reprieve before re-buttoning his shirt, repeatedly apologizing to patrons as he returns to the main floor, signaling an attempt to apologize for his transgression against Melancholy's order. The film closes out as he continues to apologize, struggling for breath.

Final Thoughts

I imagine that anyone who viewed I Saw the TV Glow understood the ending as a heart-crushing tragedy. Despite gaining the important symbols of status in Melancholy's world, it's obvious Owen feels something is missing, as many people transitioning later in life come to feel. Despite breaking the spell for another fleeting moment, he comes to understand it's too late for himself, regardless of Tara's attempts to reach out; mirroring the experiences of some trans folks who see themselves as too old to transition, due to western expectations of beauty, age, and desirability. Regardless of the brief reprieve of opening the chest wound to breathe, it's fruitless to try and fight Melancholy in such a weakened state, thus persisting on the that's harming him.

Through this ending, Schoenbrun presents and unfortunate, yet prevalent truth in that transitioning cannot always be easily attained. Tara was able to get out in small, yet important ways, due to their whiteness. They may have come back to try and save their friend, but they still abandoned their friend to the world that wished to cannibalize them. A truth became fractured and Melancholy dug his fingers even deeper into Owen, causing the fear of retaliation or retribution to become stronger than the need to escape. This reality is something white queer people fail to understand about non-white experiences with transness.

Before colonization, many cultures functioned in various expressions of gender nonconformity and creativity. While our current language feels the need to claim these experiences as trans, it's difficult to do so when those cultures didn't identify that way. In much of the media we engage in of late, we learn of activists such as Marsha P. Johnson and Silvia Rivera, two people who didn't entirely identify as trans, but due to the limitations of our current language, we have claimed them as such within the community because it represents what many strive toward and pay homage to. The unfortunate result of this is we often ascribe trans identity to cultures whose form and understanding of gender doesn't fit neatly or uniformly into western trans understanding. For further discussion surrounding this particular realm of contemporary trans discourse, I highly suggest Canadian historian Jules Gill-Peterson's A Short History of Trans Misogyny, as it further explores how mainstream trans definition cannot be applied to history, and recognizing such does not negate current identifications, rather asks us to look to the past responsibly.

Is I Saw the TV Glow a perfect representation of how race, class, and transness intersect? Absolutely not, nor is that explicitly what Jane Schoenbrun set out to achieve with this film. However, through crafting a story that approaches the highs and lows of realizing/living/disclosing transness, the subjects of race and class will inevitably come up, as these identities intersect in important ways as structures and systems continue to prompt discord and division within marginalized communities. Is it that Schoenbrun made the specific choice of characterizing Owen as Black as a means of highlighting these larger societal critiques in a film already approaching connected topics? I would like to think so. Filmmaking is an inherently political artform, and for someone as conscious about the stories they're telling and films they're making, I would not be surprised if these choices were made to tell an even deeper, multifaceted tale of suburban transness.

I'd be curious to hear if anyone else maybe caught some of this in the film. Maybe I'm simply mining too deep into a movie already chock-full of symbolism...

However, I'd like to believe that some filmmakers in our current climate seek to give voice to those whose voices have been suppressed. Perhaps Owen's characterization is what it is as a means for Schoenbrun to highlight inequities between white and non-white trans folks, opening a door for non-white directors and filmmakers to feel that much more comfortable in telling their stories and truths. Artists such as Tourmaline, with their experimentally lush Salacia, as well as the works of Isabel Sandoval, the successes of films like IStTVG show that viewers are more than hungry to see truthful, messy, unapologetically trans stories told. They reveal the myriad ways in which art can touch our souls and politicize our action and activism.

Jane Schoenbrun continues to express their talents both behind the camera and on the page, setting up a powerful career as they strive to test the membrane of cinematic storytelling as we know it.