The Fall of the House of Usher - A Collection of Thoughts

Paying homage while holding an author accountable; what a novel idea.

Like many folks, I recently binged the hell out of Mike Flanagan’s newest Netflix horror series, The Fall of the House of Usher. Being that I’ve loved much of the writer and director’s work in the past few years, I assumed a Poe-centric homage helmed by Flanagan would at the very least be an enjoyable modern interpretation of the text, sprinkling in his signature heartbreaking emotional subplots.

I was not prepared for how much I ultimately loved this series.

One of Flanagan’s strengths—at least in my opinion—is his ability to pay homage to a piece or writer while bringing something fairly new to the table. He absolutely wears his influences on his sleeves, but it never feels pandering or forced. Usher is a different animal entirely.

I’m sure we can all agree that the director’s star has been shining over the last five years. Going from a fairly low-key director, though still renowned for his excellent and unique films, to one of the most sought-after storytellers in mainstream horror, the man knows how to craft an excellent and emotional story that just so happens to cause you to pee your pants.

He additionally is adept at including subversive material amidst very classic themes and stories, and that is what brings me to this particular series. While Usher is likely the most involved and big-budget of Flanagan’s work to date, it is also his most subversive, but not entirely in the ways you may think.

Teeing Up a Conversation of Holding Classics, As Well As Their Characters, Accountable

Many writers have made the obvious comparisons to Succession, HBO’s wildly successful dark comedy reimagining of King Lear, and they sure aren’t wrong. Both Usher and Succession revolve around horrifically greedy and privileged families who have lost so much of their humanity it’s almost hilarious watching misfortune befall them. Both hold a gothic darkness in their comedy and satire. Unfortunately I have not finished Succession, but there is one thing that Usher accomplished over 8 episodes that I truly love: it held Edgar Allen Poe accountable.

When I was younger, I had field day with the classic, disturbing stories of Edgar Allen Poe, as well as the authors he inspired such as H.P. Lovecraft, Arthur Machen, and the like. My ADHD/Autism has caused me to consistently want to understand all subjects I hyperfocus on from all conceivable facets, so, naturally, I wanted to read and understand the classics that helped to foster a genre I love. What I was not privy to, or conscious of, at this formative time in my reading, is that while these authors are formidable and influential, they were also incredibly racist.

Lovecraft’s crimes are well documented. From the blatant racism of “The Horror at Red Hook” to his abominable use of cosmic terrors as a proxy for immigrants and people of color as a whole, the guy truly sucked. It’s a fact that has prompted much reevaluation of the cosmic horror subgenre over the last few decades. How many readers internalize the same xenophobia as their heroes?

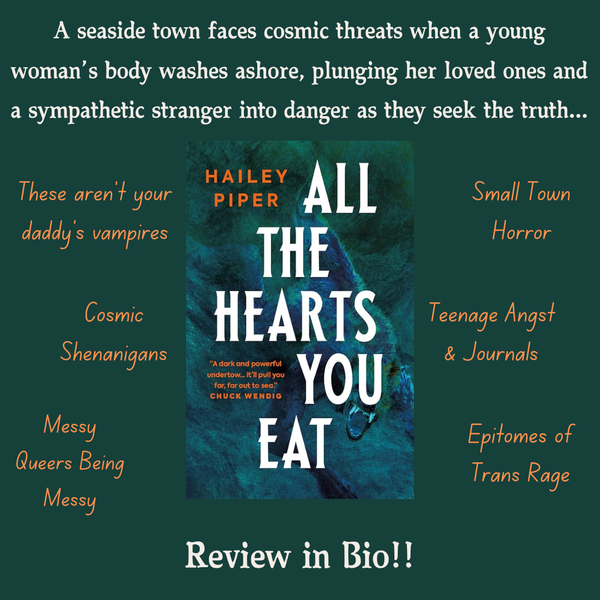

Thankfully, cosmic horror has begun to change and it’s definition is no longer as linear as its progenitors may lead you to believe. Authors such as N.K. Jemisin, P. Djeli Clark, Nadia Shamas, Hailey Piper, and a hell of a lot more, have been reconfiguring cosmic horror to broaden in the vast, unknowable terrors we weren’t meant to behold. Instead of other people, the horrors have become structural racism, grief, transphobia, generational trauma, the list goes on. Authors are now telling us to fear systems, not people.

The Horrors of Racism, and How Flanagan Seemingly Subverts Them

For Poe, he wasn’t always so blatant in his prejudice, but it was there. The main moment in Usher that I want to bring attention to is when Roderick is talking to Auggie about the family’s stoic and intimidating attorney/hitman, Arthur Pym, played breathtakingly by Mark Hamill. For those who may not be cognizant of every reference that Mike Flanagan made with his series, Arthur Pym is a character who appears in Poe’s novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket.

This story would ultimately go on to inspire Lovecraft’s most beloved work, At the Mountains of Madness, as it shares narrative similarities with Poe’s tale of exploration. It is also an early occurrence of the “Great White North” theme that would plague not only horror, but social sciences as well. When explorers began taking long ship journeys to “unexplored lands,” the north, particularly the arctic, were places that man dared not to go. Y’know, cuz it’s cold as hell, and we shouldn’t be colonizing every inch of the earth.

However, being that the farther north you travel, the trickier it becomes to reach, this led some thinkers, and by thinkers I mean, white supremacists, to believe that within those coldest regions, there must be an ancient race that came before us, who are only able to survive in those conditions, and being that it’s the north, well, obviously they must be white!!

If you’re here reading this piece, I would hope I don’t have to explain to you why this is awful. But BOY did they believe it.

Returning to Usher…Roderick makes reference to Pym’s transnational travel and how the man would tell his children stories about the truths of the earth being hollow, as well as the fact that there existed a land “hidden beneath the ice.” This refers to Thoth, which would become the theorized place that writers alleged these great white beings hailed from/inhabited. Thoth would also figure into the worlds of Theosophy, made famous by Helena Blavatsky and other “mystics” who believed that there was an astral library of all knowledge you could access, but only if you possessed the belief and power to tap into it.

I’ll let you harbor a guess: what kind of people do you think Blavatsky was often referring to? Fun fact, there are folks who believe this astral library, known as the “Akashic Records,” can help them achieve in business and wellness. Nothing like astral, spiritual bootstraps, am I right?

ANYWHOO. Auggie pushes back concerning Pym’s stories when it seems like Roderick may be lending credence to the stories, causing the man to backpedal a bit, but not before alluding to the fact that the existence of these kinds of places could explain much of the weirdness of the world. It may feel like such a throwaway moment. That this dialogue is merely to reference Pym’s story and inclusion in the show. It may be, but its delivery appears too purposeful to me.

Pym ultimately stands as one of the “saner” characters in the show, refusing to take Verna’s deal to avoid prison, realizing that only death and destruction would await him if he did. He’s a man who knows and reckons with the darkness he has seen and committed, and when the bell comes tolling, he would rather face the music in jail and inadvertently atone for his sins.

Unlike the Usher family, he is not completely blinded by greed, hubris, and ignorance at this point in his life. He has stood toe-to-toe with experiences beyond his comprehension and understands when it’s time to throw in the towel, despite his seeming invulnerability.

The inclusion is subtle, but it’s important. Roderick relaying these stories displays not only the hubris of colonization and those earliest explorers, it additionally takes a shot at the racism inherent in earlier horror as well.

While Pym stood out to me as the more glaring example of the series, the Usher’s as a family unit simultaneously display much of this too. There are Roderick’s loose love affairs that insert the siblings of color into the fold, much to the dismay of the two from his initial tragic marriage. We see several incidents of tension between the siblings, as well as microaggressions and backstabbing galore as they all vie for their own power.

Camille sets out to smear Victorine’s name by unearthing the less-than-ideal conditions of the RUE Morgue (wink) that in itself contains its own legends and myths, as well as functioning as a leg of the broader pharmaceutical empire that is responsible for the death of millions. To have her demise come at the hands of a chimpanzee under experimentation not only harkens to the “antagonist” of the original story, but makes that further statement against animal testing, as well as spitting in the face of the story’s probable racist implications as well.

As a quick refresher: “Rue Morgue” details an amateur detective, Dupin, who is attempting to solve the murder of two women, but is perplexed when the hair he discovers on the scene does not appear to be “human.” What we eventually learn is that the “murderer” was an orangutan that was brought to the Americas, existing under abuse by its owner. This story was written during a time of expansive urban growth where, say it with me, crime was on everyone’s minds, and who do we always characterize as the most common criminals???? You fill in that blank and sit with it.

Tamerlane, Usher’s first daughter, functions as a pitch perfect representation of the Paltro’s of the world, with their non-stop quest to re-purpose and re-package eugenics, racism, and fatphobia as a means of “wellness.” However, it’s the packaging of this brand that really points out the ignorance of not only her character, but the family as a whole. I’m speaking to Roderick’s obsession with Egyptian mythology and relics. The packaging of Tamerlane’s brand is a golden scarab beetle, in cheeky reference to Poe’s “The Golden Bug.”

Hollywood has a history of pointing to other cultures as the source of supernatural instances, or even simply the larger “other” of existence. This “Orientalism,” as it is laid out in Palestinian-American critic Edward W. Said’s seminal academic text, has lead to some of horror’s most unsavory tropes at the harm and appropriation of any culture that isn’t white. Roderick Usher’s ambition is built off of his obsessions with empire and the conquerors of ancient Egyptian lore, and it is within these obsessions and appropriations that his family ultimately perishes. Verna barely has to lift a finger half the time. Like numerous white celebrities of the past, they orchestrate their own undoing through ignorance and hubris.

Speaking of Verna…

How Verna Functions As One of the Best Horror “Villain” Metaphors for Battling White Supremacy on TV

To close out this piece, I want to talk a bit about Carla Gugino’s positively mesmerizing turn as this season’s big bad, Verna. Not only were we blessed with some of Gugino’s most spine-tingling performances to date, but Flanagan provided a threat that stood as less of a villain, and more of a cosmic superhero, of sorts.

Though Verna is often alluded to as the “Raven” of this series, I think the bombshell revelations delivered to the Ushers at the halfway point concerning Verna’s involvement with many prominent politicians and thinkers prefaces larger cosmic implications. I was almost afraid she would be billed as an ancient Egyptian deity as a means of tying it back to Roderick’s obsession, but that felt too reductive to what it is that Flanagan was trying to say with this series.

Instead of Verna simply functioning as an agent of judgment, I would assert she’s rather an agent of Chaos, in its purest form. Legions of writers and philosophers have talked at length concerning how much chaos doesn’t care about our conceptions of Free Will. Chaos will always be lurking around the corner as a means of muddying our plans and wishes for stability, but also in plans toward dominance as well.

Many of the people who hold power over the populace like to believe they’re the smartest and most cunning people alive. Heck, it’s ultimately why they rose to—and remain in—power, right? We clearly witness this in Roderick and Madeline’s behaviors throughout the course of the story. The ultimate “Cask of Amontillado” death of Michael Rucco’s Rufus Griswold represents not only the Usher’s ultimate revenge upon the Griswold family, but sets the path for their growing arrogance as their empire grows. It was almost the perfect crime—but then Chaos came knocking.

Verna’s ensuing assistance acts as their ultimate armor, while simultaneously functioning as their eventual achilles heel. Verna as Chaos is all too aware of the greed and hubris that can appear and metastasize in humans, hence how she is always able to infiltrate the rich and powerful. These folks are primarily focused on achieving and maintaining power, which in her cosmic way, is able to gift this dream to them. While this could paint Verna as a seeming agent of white supremacy, her more obvious intentions are to inject chaos into the plans/dreams of these individuals and allow them to precipitate their own descent.

This is what makes Verna’s moment with Lenore so heartbreaking and poignant. It’s evident that Lenore must perish in order to become “Nevermore,” the catalyst to the ultimate destruction to the Usher bloodline. We witness the pain in Verna’s eyes when she comes to take the girl because while she is an omniscient force, she’s not the monster that this horror framework would lead us to believe. Her compassion and sense of justice rings throughout all eight episodes. Harkening back to my thoughts on Arthur Pym, Verna offers him the ability to embrace Chaos and avoid jail time, as well as respects his refusal to do so. She attempts to warn Morelle about the oncoming chemical orgy in episode two, while luring the innocent workers out of the building before the incident. She even imparts to Lenore the beautiful future that her mother will create after her loss. Verna is not evil, but she must allow the universe, as well as her own deals with humans, to play out exactly as they should.

Wrapping Up—FINALLY!!

Taking all of these things into consideration, it’s evident that Flanagan knew exactly what he was doing when writing this “antagonist,” and how her presence would bring the entirety of Usher’s message into perspective. What starts as a conventional homage to one of the genre’s most looming and prolific progenitors, comes to an end in a way that much of contemporary horror is doing today. It’s taking note of its influence AND holding the initial works up for scrutiny. It’s using the text as a means of highlighting where we’ve arrived to in our constantly changing world.

The Fall of the House of Usher functions as a love letter that additionally raises concerns in the relationship. And yes, these messages and topics are being presented by a wildly successful cisgender white man, so of course not everything about this show is pristine. My point lies in the fact that this wildly successful director and writer decided to utilize his influence to tell a brilliantly nuanced fable/parable that rightly should scare the living hell out of everyone who watches it, but it’s that further step of scrutinizing the pitfalls and harm of the original texts that drives it all home. Flanagan, as well as many other writers and indie directors, are using their platforms to learn from our influences, while simultaneously seeking to flip the script, building tenable bridges to the stories we should and need to be telling right now.

It’s incredibly refreshing and I hope that others follow his lead.

For those who have made it this far, thank you so much!! I had so many thoughts swimming around in my brain for weeks regarding this series, and these are merely the tip of the iceberg. Like much of Mike Flanagan’s output, I greatly loved this piece, especially after the emotional devastation upon my soul that was Midnight Mass.

I imagine I’ll be talking and thinking about The Fall of the House of Usher for a long time, so this likely isn’t the last you’ll read on the subject, but it means the world to me that you would take the time to read these initial thoughts. If you know of anyone who also loved this series and think they’d enjoy this review, please share!

Stay spooky, my friends.