The True Violence of Mundanity - A Look at Elle Nash's "Deliver Me" & Charlene Elsby's "The Devil Thinks I'm Pretty"

Hell hath no fury like a woman underestimated.

I often like to believe that I am not a wimp when it comes to extreme horror. Bill Martin didn’t raise no weenie.

All joking aside, extreme horror is a genre I love, but sometimes struggle with. I’m a tender soul, so sometimes plumbing to the depths of complete human depravity presents challenges. However, under the right authorial voice, extreme horror has often offered some of the most searing commentary within our wretched darkness.

The genre stands the test of time, with varying degrees of success and empathy, but 2023 has seen the subgenre flourish with hundreds of stories doing their best to make some twisted sense of this bizarre world. And hopefully draw some blood in the process.

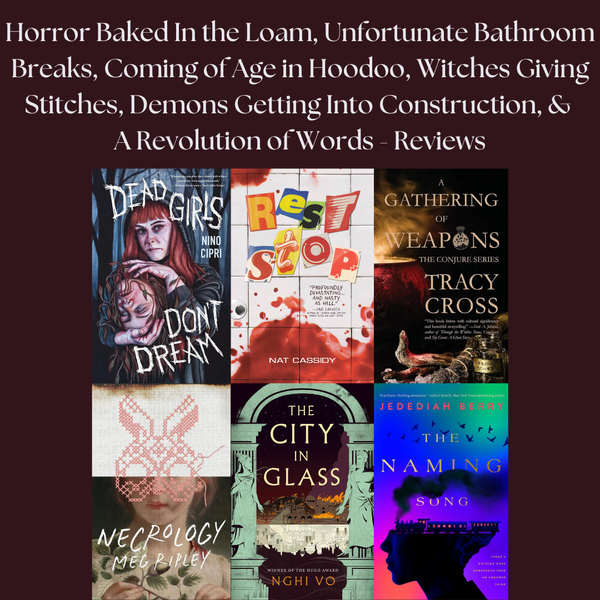

Two recent examples that I’ve greatly enjoyed (though my wimpy self uses “enjoy” reluctantly lol) are Charlene Elsby’s novella The Devil Thinks I’m Pretty and Elle Nash’s newest novel, Deliver Me.

Oh, Here We Go, Summarizing Again!

Devil follows the mundane misadventures of a young girl whose class and upbringing has positioned her as an outsider in her small trailer community and beyond. Where said positioning does offer her a unique sense of understanding about the world of her community, as well as the socio-political follies of her fellow classmates, these understandings mutate into her own quest for a sense of control and domination.

I won’t say much else, because part of what makes Devil so captivating and outstanding is the prose’s ability to cause disorientation, though the disorientation is the point. There’s a sense of uncertainty throughout, leaving our narrator’s voice both comforting and intensely unsettling. When this book goes for its checkmate, you not only experience whiplash, but complete and utter shock as well. Elsby’s prose and plot structure is finely tuned and tightly executed. Experiencing this novella is what makes it as unique as it is wickedly brilliant.

In Deliver Me, Dee-Dee works at a Missouri chicken processing plant. Each day she comes home to her boyfriend Daddy (or David) who holds a specific pleasurable interest in bugs, as well as enduring invasive phone calls with her aggressively religious Pentecostal mother. When her childhood friend returns to her life, moving into the apartment directly above Dee-Dee’s own, things begin to unravel for this woman as old insecurities arise and send our narrator down a dark road of obsession and desire.

Much like Elsby, the voice of Dee-Dee’s character slots easily into the “unreliable narrator” trope. However, this is not a means of vilifying Dee-Dee, but to unfortunately illustrate how much of this poor woman’s emotional, familial, religious, and class trauma has effected her own sense of self, as well as the ways in which she connects to the world and people around her. Deliver Me is very much a social horror at its core, leading the reader down consistently transforming hallways of grief and uneasiness until it’s gear-screeching finale.

Mundanity As a Form of Violence, or, How to Write a Convincing Break From Reality

As readers—and humans—we typically like for there to be an inciting event or reason for our characters or villains to turn into the devious threat they are. Whether it’s in cinema or literature, we’ve seen countless “origin” stories for the bad guys. This is typically meant to function as a shorthand so that audiences understand their ascent or descent into villainy.

There is also something to be said about the books/movies/television shows that seek to plunge deeper into the emotional depths, presenting characters who are far more complex than simple good/evil binaries. Breaking Bad is a successful example of this, charting Walter White’s descent into greed and violence from a “mild-mannered chemistry professor.” Spider-Man: No Way Home sought to rehabilitate past multiversal villains, playing with the concept that villains can change if given the chance. Well, that is unless you’re Norman Osbourne and are just too far gone…

My point is that no writer is unfamiliar with this kind of character framing. We tell these stories as a way of working through much of what we fear concerning our own moral good. Women and Feminine writers has been exercising this for decades, especially when it comes to the “bad woman” or “good for her” plotlines. There’s something to be said for what Elsby and Nash achieve through their respective protagonists, pushing further than the pervasive “I’m not like other girls” storytelling.

Essentially: these two are women who have seen the darkness and regardless of intent, have leaned into it with open arms. We may think that their traumas are what lead to their extreme actions, but that’s only part of the larger structural issues, in this case, class.

Have you ever been poor and bored? I mean really poor and really bored. Mundanity is not as simple as lethargy or laziness, or work vs unemployment. In America, we sure love a bootstrap mentality that waves away all those pesky structural issues that keep folks in poverty. Simply work harder and that effort will be rewarded. Never solicited or taken advantage of, no no.

Elsby’s narrator is a high schooler. She’s not an adult weighing in on death and taxes, so there’s a sense of “freedom” to her day-to-day. However, due to the traumas she has faced at the hands of her placement in the class scale, she has paid witness to the trivialities of social capital. As an outsider, she is able to use these “rules” against not only her colleagues, but the adults who are supposed to know better than her. Mundanity has allowed her the time to reflect on much of what can cause a mind to spiral into unchecked nihilism, or even cruelty.

Not everyone goes in this direction, obviously. I have always been fairly lower class and at times found myself considering the void. It’s deceptively comforting to eschew social grace and order as a means of entertainment or even power acquisition. While I have uncovered some of the most unsavory aspects of American culture for myself, it has caused me to want to dismantle said structures for the betterment of the world, not simply give up on it altogether. The brutality of Devil is meant to highlight that mundanity, not as a means to point toward youth culture and say, “See?? Look what happens when these kids have too much time on their hands!”, but to lay out this character’s particular societal algorithm and show us how the brutality came to be. Its humanity is meant to exist alongside its horror.

The same can be said for Deliver Me. While Dee-Dee very obviously has her own struggles with mental health, those struggles are further exacerbated by the conditions of her class existence, as well as the trauma and grief that sometimes shadows motherhood in a country that doesn’t provide pregnant people with the resources they need.

Being that Deliver Me is a novel-length book, Nash takes her time in fleshing out Dee-Dee’s experiences and hurts. We are meant to understand her humanity just as much as her desperation continuing deeper into the story. She is a human in the rawest sense, as she, like the narrator of Devil, finds herself pushed to insane limits to achieve her own broken sense of normalcy in a world that continues to shoulder onward, despite the mechanisms propelling it having failed decades ago. Where the shock of Elsby’s novella is very abrupt and disorienting in it’s format, Nash leads the audience, reluctantly, toward the heartbreaking conclusion. Because as horrific of a body-horror tale as this is, it is so very heartbreaking at the same time.

Mundanity in Deliver Me is even more pervasive and agonizing, as we follow Dee-Dee through her seemingly textbook days of work and home. Yet, as the plot lingers forward, you feel the pace increase as further unease is revealed along the way. In her mundanity, Dee-Dee is allowed the same time to revel in her disappointments, regrets, and hurts, which only adds to her growing delusions. If we lived in a world where people received the correct healthcare and focus on mental health, would these kinds of narratives need to exist?

Alright, Violet, What’s the Point? I Gotta Get Home…

This has been a lot, and hopefully, has left you with some morsels of thought to chew on as you go about your day. Social Horror exists as a subgenre because there is so much about the ways we excuse our treatment as citizens that is freaking horrific! This piece is not meant to provide cynical commentary on two earnestly bleak books. To deem them as merely bleak is a disservice to these immensely talented writers, as well as the hard work they put into creating two very stark pieces of social commentary.

While some will always view horror as cheap thrills and balk whenever critics analyze deeper contextual meaning—”JEEZ WHY IS HORROR SO WOKE NOW??”—the genre will always be a site of political and subversive thought. It’s merely that this current wave of writers are tired of being solely contextual and want readers to walk away with the raw emotional need of the text’s central message. Not all authors focus on this, obviously, but for those who do, there’s a further enrichment to being both horrified and struck by their care.

Both of these novels are special gems in the last few months of horror titles. It’s a circle that continues to widen with works such as Tim McGregor’s Wasps in the Ice Cream and Scott J. Moses’s Our Own Unique Affliction. These authors bring horror to our most human level of mundanity in working-class towns, creating a broader scope of experience at the intersections of trauma and grief, as well as how they ultimately effect us as people.

Despite Devil and Deliver Me being my introductions to both of these writers, I am very excited to explore their previous and future works. Who knows what other devilish darkness awaits inside…

Massive thanks to Charlene and Apocalypse Party for sending me an ARC of The Devil Thinks I’m Pretty, as well as to NetGalley and The Unarmed Press for providing me with an e-ARC of Deliver Me.